In Egypt, one of the forms of entertainment you may encounter in tourist shows is the tannoura. This consists of whirling to music, which originated as a Sufi ritual, and today in Egypt has become an elaborate artistic performance.

How Whirling Started

During the 13th century, the legendary poet Mevlana Jalaleddin Rumi made his way to the town of Konya, Turkey, where he settled. Rumi was a practitioner of Sufism, which is an implementation of Islam that embraces mysticism. He believed in music, poetry, and dance as being paths for connecting with God.

Under Rumi’s leadership, the Mevlevi sect of Sufism arose in Konya, Turkey. Its participants used whirling as their way to let go of their ego and connect with God. The photo below shows the garb that Turkish dervishes wear for their semas (whirling rituals).

After the Ottomans conquered Egypt in 1517, Turkish cultural influence began to make its way south to Egypt, and that included the Mevlevi whirling dervish sect.

The Egyptian Side of Whirling

Egypt’s tannoura performing art owes its origin to the Mevlevi practice sarted by Rumi, but modern-day performances of tannoura are designed to serve as entertainment, and therefore they incorporate showmanship techniques. Some retain the Sufi music and spiritual tone, while others have moved into a more secular direction.

The word “tannoura” means “skirt” in Arabic, and in this context refers to the skirts worn by the men. “Tannoura” has also come to refer to overall performance, and also the men wearing the skirts. The Egyptian tannoura garb is very colorful, to enhance the spectacle.

Although Sufism exists in Egypt, the whirling tradition of the Turkish Mevlevi sect is not strong there. Instead, Egyptian Sufis prefer other movement formats.

In an Egyptian tannoura show, the whirlers manipulate the skirts to produce a variety of visual effects. Typically, the performer wears more than one skirt, which allows for the outer layers to be removed and used in the dancing. One level of skirt is sewn together at the outer edges, creating a cone effect when the top layer is raised above the head.

Another effect that tannoura performers create with their skirts is that of a whirling disk:

Cairo’s Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe

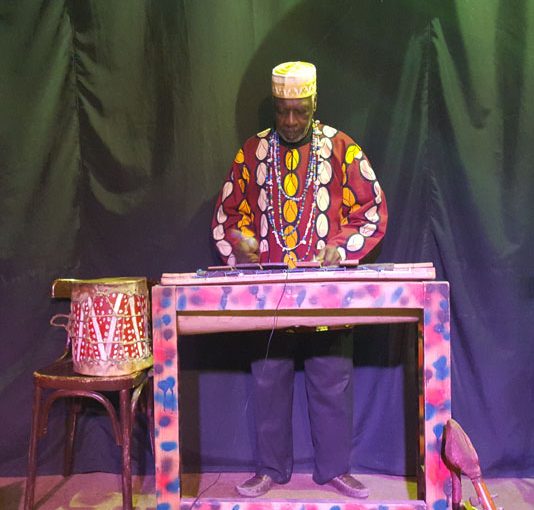

The Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe show at Wikala al-Ghouri is sponsored by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture. It begins with a performance of spiritual Sufi music, featuring in turn different musical instruments, including the mizmar (shown below), the nai (a type of flute), the percussion, and the singers.

After the musical introduction to the show, the Sufi dancers take the stage. These men wear white gallabiyat (robes) with a vest over them. Their movement is choreographed for the stage; however, it is based on authentic Sufi ritual movement.

The dance performed by these men in the white gallabiyat is typical of traditional Egyptian Sufi movement such as could be seen at a zikr (ritual) during an Egyptian moulid (saint’s day celebration). As they complete their featured segment, the tannoura enters the stage wearing a more colorful ensemble of multiple skirts over trousers.

The focus turns to the tannoura, as the Egyptian-style Sufi dancers to perform in formations of a line behind him, or a circle moving around him. Often, the tannoura will begin the performance with a group of brightly-painted frame drums in his hands, holding them in a variety of formations while continuously whirling. Eventually, he hands these drums off to one of the other men while still continuing to turn.

He then loosens the ties holding one of his skirts in place, and raises it up off of the ones below. At this point, he may hold it in various formations such as those shown earlier in this article, always while continuing to turn in place.

Eventually, this performance draws to a close, and the tannoura leaves the stage.

Next, a group of three other tannouras enters the stage. They too use their skirts to create a variety of visual effects as they whirl. For example, these two are rotating their skirts around their necks as they turn.

If you’d like to find this group on social media, click here for their Facebook page.

Other Tannoura Performers

Tannoura performers appear in a variety of shows throughout Egypt, including Nile dinner cruise boats, nightclubs, and other entertainment environments. These shows often create a more secular feeling than those of the Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe.

The tannoura performers in these other environments often use secular music instead of the traditional spiritual Sufi music. They typically appear as soloists, and may use pre-recorded music instead of live musicians.

It has become trendy for many of these performers to have an assistant dim the stage lights part of the way through their shows, at which point they turn on LED lights which have been sewn into their costumes.

I have also seen tannoura dancers pull an Egyptian flag out of their vests and hold it high as they whirl.

Closing Thoughts

I have gone to see the Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe perform about 15 times since the first time I saw them in 1999. Sometimes I’ll go twice during the same trip to Egypt. I have never grown tired of it. I find the spiritual Sufi music to be uplifting, and the dance performances to be mesmerizing. Often, after attending a show, I find myself feeling calmer, less stressed, and peaceful.

I also enjoy the individual tannoura performers that I have seen in Nile dinner cruise shows and “Egyptian party” shows at hotels. The flavor is different because of the more secular tone, but it’s always fun to see the showmanship ideas that the performers add to their whirling.