The stereotype of “Pharaonic dance” with the bent elbow and wrist arm positions is deeply embedded in U.S. culture, and has been since about the 1920’s. Buster Keaton does those arm positions in the 1918 silent movie The Cook which also stars Fatty Arbuckle.

These arm positions have also shown up in cartoons, countless “Pharaonic” dance performances, and the music videos such as the Bangles’ “Walk Like an Egyptian”. When Irena Lexova wrote Ancient Egyptian Dances in 1935, her initial objective was to examine whether this stereotype was indeed accurate.

For many years, I’ve been looking for evidence showing that “Pharaonic arms” actually were part of dance in ancient Egypt. On my many trips to Egypt, I have looked for images on temple and tomb walls demonstrating such a pose, without finding any. I have also dug through books and articles about ancient Egypt. I’ve discovered many other dance scenes with other postures, but not the right-angled joints. In her book Ancient Egyptian Dances, Irena Lexova stated her conclusion that this pose came from the Etruscan civilization (in what is now modern-day Italy), not Egypt.

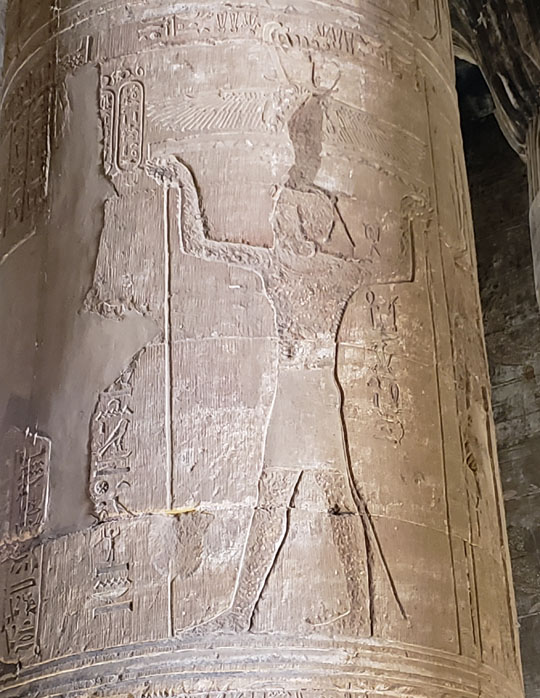

So imagine my surprise in February 2017, on my 12th trip to Egypt, when I spotted one at the Temple of Horus in Edfu, Egypt! This was my 7th time visiting that temple. Why didn’t I see this on any of my previous 6 visits?

And once I found it, I discovered it appeared in more than one place. Here’s a column showing the dancer facing the opposite direction.

I asked the Egyptologist who was acting as our tour guide whether this was a “dance” or some other activity. (In Egypt, in order to become a licensed tour guide, an individual must obtain an advanced degree in Egyptology as well as meet some other qualifications.) He said yes, it was a liturgical dance being performed by a priest. The vertical lines coming down from the hands represent a stream of liquid being poured from the hands. So, what does this image suggest about the stereotype of the “Pharaonic” wrist and elbow posture?

- This dance style is done by men. I have not yet found images of women doing it.

- The “Pharaonic” arm position was used for religious ritualistic dance.

- This dance was known to Egyptians as of 200 BCE, because construction on the temple building that stands at Edfu today was begun in 237 BCE. I haven’t yet found earlier images of it.

- This scene was shown in a temple that was built during the era of the Greek Pharaohs. This makes me wonder whether this dance position was indigenous to the Egyptians, or whether it was introduced by Greek priests. I guess it’s a question for further research.

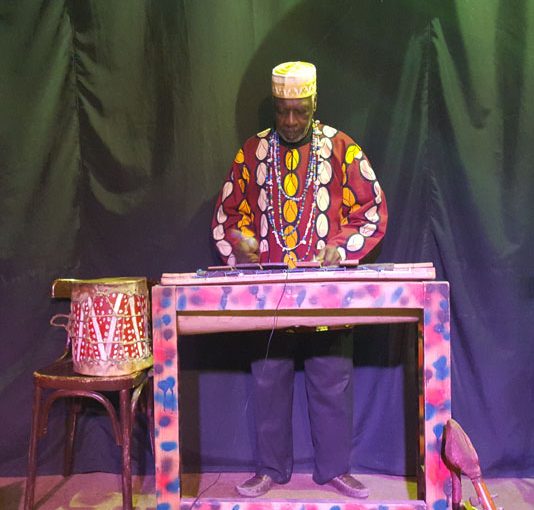

When I returned to the Edfu temple in 2019 for my 9th visit to it, I once again saw the images shown in the photos above, but then was astonished to discover there were more such images at this temple! My guide confirmed that yes, these are also images of sacred dance being performed by priests. This time, instead of appearing to pour liquid from their hands, they appear to be holding something, perhaps daggers or feathers. How could I have missed these on my first eight visits to this temple?

I still have never seen this type of arm position anywhere in Egypt other than the Edfu Temple. I realize it’s possible that it appears elsewhere, but so far I haven’t found it. I’ll keep looking.

I said for many years that I didn’t believe there was ever a bent wrist-and-elbow dance posture in ancient Egyptian dance because all of my prior research seemed to indicate there was not. It seems I was wrong. It’s time to update my thinking!