Egyptians often refer to their homeland as Masr Om el Dunia, which means “Egypt, Mother of the World”. Because of this, even since ancient times a fellaha (peasant woman) has been used in Egyptian art as a symbol of fertility and giving life. In my travels to Egypt, I have seen a number of beautiful fellaha statues in public places.

Nahdet el Masr (Awakening of Egypt)

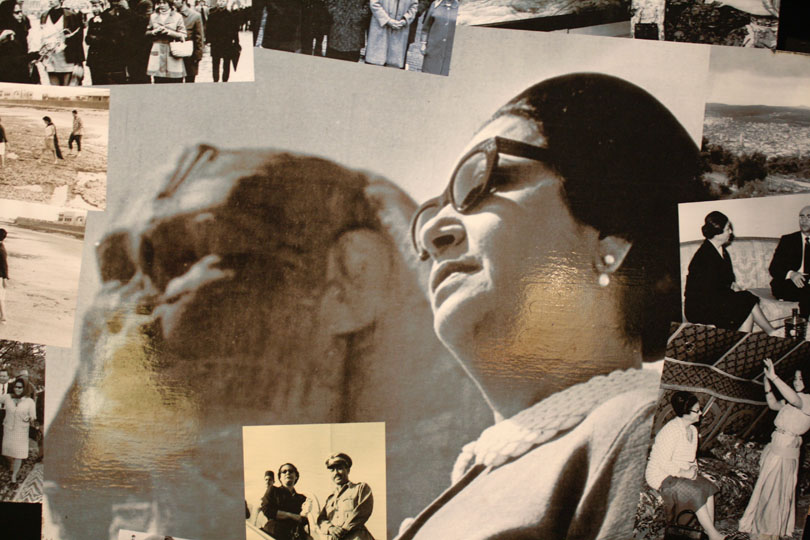

The most famous of the fellaha statues in Egypt is the one at the top of this post, which is known as Nahdet el Masr (Awakening of Egypt). It stands in front of Cairo University, near the Giza Zoo. The statue, made from rose granite, was unveiled in 1928. It symbolized Egypt’s struggle for independence from Britain following World War I and the 1919 revolution.

This statue uses both a Sphinx and a fellaha to represent Egypt. The woman unveiling her face represents Egypt’s post-revolution revival, while her companion the Sphinx recalls the greatness of Egypt’s history. (In Arabic, the Sphinx is called Abu el-Hool, which an Egyptian taxi driver told me means something similar to “father of all”.) With these images together, the statue celebrates Egypt’s glorious past while looking ahead to the future. The statue was erected facing east so that each day the sunrise would strike it as if to reawaken Egypt.

The sculptor who created this statue was Mahmoud Mukhtar, a highly respected Egyptian artist of the early 20th century. On May 10, 2012, Mukhtar was honored with a Google Doodle which features Nahdet el Masr to commemorate his birth date.

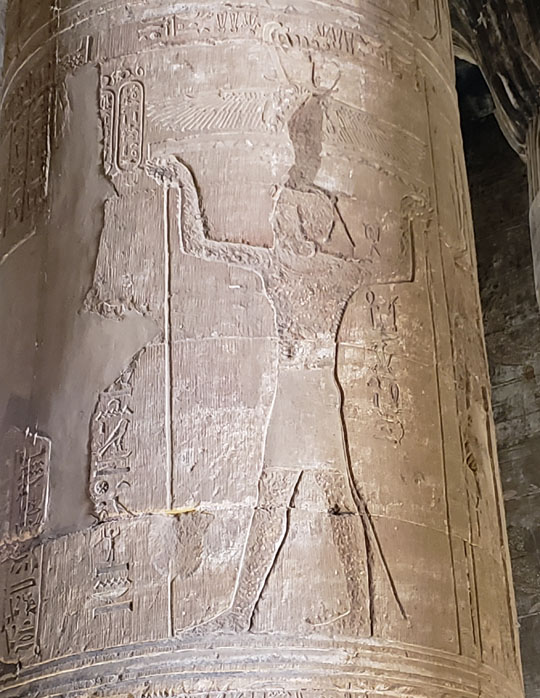

The Agricultural Museum

The Agriculture Museum in Cairo, Egypt is a treasure that most tourists visiting Egypt have never heard of, and never been to. It resides inside a former palace, so even the architecture is well worth taking a moment to enjoy. I think maybe the museum opened in the 1950’s, but I could be wrong about that. The museum is near the Giza zoo and the Cairo Opera House.

There are two beautiful fellaha statues outdoors on the grounds of the museum. Both celebrate the role of women in the agricultural lifestyle.

Khayamiya

There’s a street in Cairo known as sharia el khayamiya, which means “the street of the tentmakers”. Tent work is a textile art that consists of using applique to create designs on a sturdy fabric backing. I was delighted to see this khayamiya artisan’s piece with an image of a fellaha on it.

Basma Hotel in Aswan

When I go to Aswan, I enjoy staying at the Basma Hotel. Its beautiful courtyard features a large swimming pool, adorned with a statue of a fellaha carrying a balas (water jug). A walkway leads from the edge of the pool out to the statue, so it is possible to pose for a photo with her.

The Fellaha Statue that Never Was

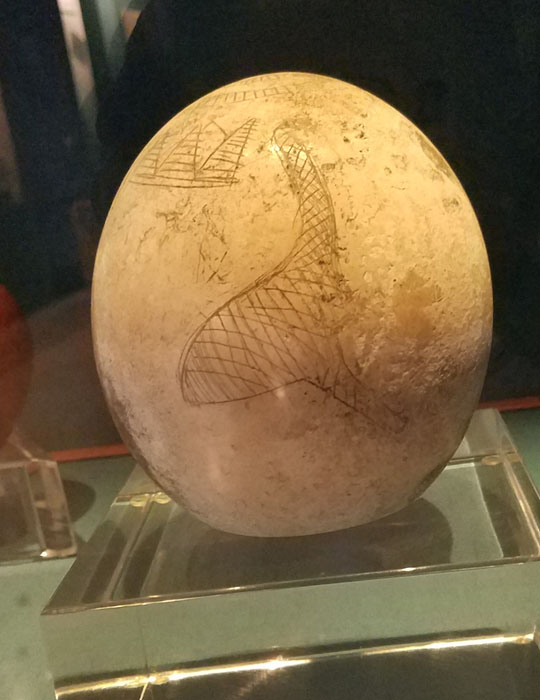

Today, we know the French sculptor Auguste Bartholdi as the artist who created the Statue of Liberty. What many of us don’t realize is that in 1867 he had approached Ismael Pasha, the Viceroy of Egypt, with the idea of creating a massive statue of a fellaha holding aloft a torch which would be placed at the entrance of the Suez Canal. The statue would be called “Egypt – Carrying the Light to Asia”, and it would also serve as a lighthouse.

Bartholdi submitted several sketches in 1869 for his proposed statue, hoping to receive a commission in time to complete it for the Suez Canal’s opening. Unfortunately, the project never went forward due to a lack of funds to pay for it.

I hope someday to visit the Suez Canal, and when I do, I’ll take a moment to fantasize about the fellaha statue that Bartholdi had dreamed of creating for it.

About My Egypt Travels

For several of my trips to Egypt, I have traveled with Sahra Kent, through her Journey Through Egypt program. I discovered the fellaha statues shown in this post through traveling with her. I highly recommend the Journey Through Egypt program to anyone who is interested in a cultural perspective of Egypt.